One of the projects under the Global ROS1 Initiative is the creation of a ROS1 Biorepository, that will collect tumor tissue and other specimens from patients who have ROS1-fusion+ cancers (referred to as ‘ROS1+ cancers’ going forward). Some of this patient tumor tissue will be used to create preclinical cancer models (such as mouse models or cell lines in a lab dish) to research ROS1+ cancer.

Having more preclinical models of this rare cancer will greatly accelerate research. Preclinical models have long been used to study molecular mechanisms of disease, research biologic processes, and develop new cancer treatments. Researchers need many different preclinical cancer models of ROS1+ cancer from many different patients to develop more effective treatments that are likely to work for most ROS1+ patients. These models are especially important for assessing the effectiveness and toxicity of combination therapies before testing them on patients. We need lots of ROS1+ tumor tissue samples because these models are difficult to create, and a given tumor sample does not always generate a useful model.

What is the ROS1 biorepository project?

The biorepository project aims to accelerate research into rare ROS1+ cancers by creating more ROS1+ cancer models. It will create a process that allows ROS1+ patients to donate live tumor tissue from an already-scheduled biopsy or surgery, and move those tissues quickly (within 24 hours) to a lab that has technology to create cancer models. The models will be made available to academic researchers and pharma, at minimal cost to study cancer biology and test new drugs that might be useful in treating ROS1+ cancer.

Why is this project needed?

Because ROS1+ is a rare cancer, only a handful of researchers currently study it, and their research clinics don’t see many ROS1+ patients. As a result, only a few ROS1+ cancer models exist. Thus far, most diagnosed ROS1+ cancers are lung cancers, and biopsies of those cancers typically generate only small tissue samples that aren’t large enough to generate cancer models. In addition, ROS1+ cancer models are difficult to create—the collected tissues sometimes die despite best efforts, which limits the amount of research that can be done with them. Without a large selection of ROS1+ cancer models from diverse patients, researchers and drug developers are less likely to find treatments that are effective and tolerable for most ROS1+ patients.

The ROS1der patient/caregiver group currently contains over 140 patients with different types of ROS1+ cancers (e.g., lung cancer, melanoma, angiosarcoma) from 18 countries, and our numbers are increasing. With this large number of ROS1+ cancer patients, we hopefully can generate many useful tissue samples and increase the odds of creating successful tissue models.

Deciding to donate tumor tissue is not something patients undertake lightly. It requires a personal commitment (as well as planning and coordination) during a time when a cancer patient is dealing with invasive medical procedures and the anxiety of possible or confirmed metastatic cancer progression. This project will help ease the process by allowing patients to commit to tumor donation ahead of time, when stress levels are reduced and the patient and their healthcare provider have time to have the right conversations and make the necessary arrangements. And even after patients join the project by signing a consent form, they can still choose later not to donate tissue.

What are cancer models? Why are they useful?

Preclinical cancer models are clumps of cancer cells that exist either in a lab petri dish, or in animal models such as mice. The best models are derived from actual patient tumors. Sometimes these models include additional cells, molecules and fluids (the “microenvironment”) that exist near cancer cells in the human body—white blood cells and other immune system cells, proteins, bits of DNA, and such. These models are kept alive and used to create more cancer cells for current and future research. Amongst ROS1+ cancers, each tumor can have subtle differences, so it is important to have multiple models to ensure that any treatments that are identified can work for many types of ROS1+ cancer.

These models are valuable tools for cancer researchers. Academic cancer researchers use them to study ROS1+ cancer cell biology, identify new cancer treatments or treatment combinations, and understand mechanisms of resistance. Pharmaceutical companies use these models as the final test before deciding to commit to a clinical trial of a new drug or combination. Diagnostic companies use these models to validate or develop new genetic or other biomarker tests.

What types of ROS1+ cancer models will this project create?

The two types of tissue models our vendors will create are ROS1+ cancer cell lines and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mouse models. These models allow us to understand the biology of ROS1+ cancers and how to stop their growth or kill these cancer cells. Each model has its own advantages and disadvantages.

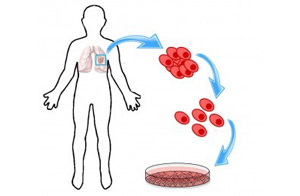

Figure 1. Making a cell line tissue model.

What are cell lines?

Cell lines are clumps of cancer cells grown in tissue culture dishes in the lab. To create a cell line, fragments from a patient’s tumor are put in cell culture media in a special incubator (see Figure 1), then routinely monitored until cell lines are detected. The cells have been treated so they will continue to reproduce instead of dying at their pre-programmed time. This creates an ongoing source of cancer cells for research. You can learn more about creating cell lines in this Science magazine article.

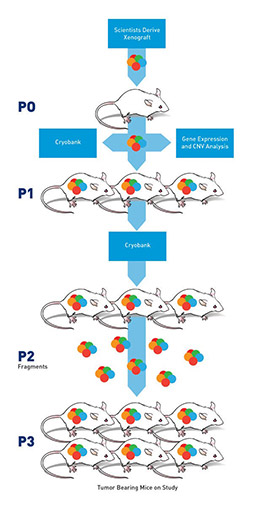

Figure 2. Making a PDX tissue model.

What are PDX models?

PDX models, or patient-dervived xenograft models, are models derived from human tumor tissue grown under the skin of specialized mice whose immune systems have been severely compromised. The compromised immune system helps ensure the mouse’s body will not attack the human cancer cells. To create a PDX model, scientists cut a human cancer tumor into pieces, mix it with a chemical that helps the cancer cells survive, and then implant the pieces under the skin of many mice. Sometimes these don’t “take” but often, each fragment grows. Once the tumor reaches a certain size, it is removed from that mouse, chopped into pieces and put into more mice. This process is repeated (see Figure 2) until there is enough tumor tissue to put into 100s of mice, each with tumors nearly identical to each other and to the original human patient’s tumor.

What are the advantages and drawbacks of these models?

Researchers often use cell lines initially to test hypotheses about a cancer, and then later use PDX models to do large-scale drug testing to confirm their cell line results. At present, neither model can be used to test immunotherapy drugs because neither include a functional human immune system.

Cell line advantages:

They grow fast and are relatively easy and inexpensive to store and transport. They can be used to rapidly and cheaply test multiple drugs or drug combinations. They can be used to study cancer cell biology (for example, what causes resistance mutations) and explore different ways to kill the cancer cell.

Cell line disadvantages:

The processing used to make the cells grow perpetually may favor some cells and allow others to die, so the resulting model does not precisely resemble the original tumor. The cells change over many generations, so their characteristics may become significantly different than those of the original tumor cells. They do not include the tumor microenvironment.

PDX model advantages:

PDX models are thought by some to more faithfully represent a human cancer tumor. They may preserve some of the tumor microenvironment. They are grown in a living host instead of a lab dish. They can be used to simultaneously evaluate the effectiveness of different drug or drug combinations in a living organism, and provide in-depth understanding of tumor response to experimental therapies at a fraction of the cost of a clinical study. They can be used to identify potential biomarkers of drug response or resistance. They might allow tumor tissue to propagate longer than cell lines with fewer genetic changes.

PDX model disadvantages:

They are more costly and time-consuming to make and maintain, because developing immune-compromised mice is expensive, the mice need time to grow, and caring for the mice requires housing and feeding. Because they are more costly and time consuming, they are not practical for large-scale testing of multiple drug combinations. They might tend to propagate only the human tumor cells that are compatible with mouse biology.

How long does it take to create a cancer model?

Successful creation of cell lines and PDX models will require four to twelve months after the tissue donation is received.

Will my tissue donation result in new treatments for me?

No, these models will not generate new treatments fast enough to help individual donors. Because creating the models, conducting research, and testing new drugs takes years, the donated tissue will, most likely, not generate new drugs in time to help patients who currently have ROS1+ cancer. However, you will be helping to accelerate discoveries and new treatments that will improve outcomes for future ROS1+ cancer patients. Please donate only tissue you do NOT need to make decisions about your own cancer treatment.

What kind of tissue is needed for donations, and how much?

Fresh ROS1+ tumor tissue increases the chances of creating successful cell lines and PDX models. Ideally, the lab begins the process of creating the tissue model within 24 hours of collecting the tumor tissue. The more tissue, the better the chance of success–at least three biopsy cores of tissue (using 19 gauge needles) are needed.

Other types of specimens may also be useful. We are evaluating whether the biorepository will also collect the following

- Pleural effusion fluid (for creating cell lines and PDX models)

- Frozen ROS1+ tumor tissue (for extensive genetic analysis–the genetic material is better preserved)

- Formalin-fixed ROS1+ tumor tissue–the typical storage method for pathology specimens (if this is the only tissue available)

- Blood, urine and saliva samples (for studying circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells)

- Healthy tissue collected at the time of biopsy or surgery (can determine which mutations are present in the patient’s healthy cells)

Will all donations create a successful cancer model?

No. Success depends on many things, such as the amount and quality of the tissue, and the time elapsed between harvesting the tissue and starting the tissue model process. Estimates suggest 20-50% of donations result in a successful model.

Who can donate tissue?

At present, any living ROS1+ cancer patient whose tissue was collected in the USA may donate tissue and specimens. However, because the tissue must be in the lab and ready for processing within 24 hours of harvesting, transportation and/or shipping constraints may make it impractical for some patients to donate. The Addario Lung Cancer Foundation is working to establish a system that can rapidly ship tissues from your site of biopsy to the lab that is building the ROS1 model.

We are currently collecting tissue only within the USA because many national and international laws prohibit transferring biospecimens across borders. We are exploring ways to ensure all ROS1+ patients, regardless of where they are treated, will have the option to donate tissue and other specimens to this project. Hopefully the project will eventually also include a process for patients or their family members to donate a patient’s tumor tissue after they die.

If I want to donate tissue, what must I do? What will be required of me?

Prospective participants must sign a consent form to indicate their interest in donating, and inform the project when they have an upcoming biopsy or surgery. We will work with you and your healthcare provider to make sure your tissue gets to the right place on time. We will also collect your cancer medical history records so that researchers will have necessary background information about the tumor tissue (your personal identifying information will not be shared with the tissue model vendors). Donors will not have to bear any costs of the donation process. We are currently developing the consent form and the donation process materials which will clarify the process. After signing the consent form, you may still choose not to donate (but we hope you won’t).

Will the resulting cancer models and associated clinical data be available to all researchers?

Yes. Our goal is to make the resulting ROS1+ tissue models and associated data available to all interested academic researchers and pharma for minimal cost. The idea behind all projects under the ALCF Global ROS1 Initiative is to make data and resources ‘open source’ to accelerate further research into this relatively rare molecular subtype of cancer.

Who will create the cancer models?

The Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation is currently negotiating with academic and commercial labs that create cell lines and PDX models.

When will the biorepository begin accepting tissue donations?

We plan to choose the model vendor(s) by March 3, 2017, and then begin finalizing consent forms. Distributing & collecting consent forms will be an ongoing process, but we’d like to collect as many as possible in the first few months to help ensure most ROS1ders will be able to make use of this tissue donation opportunity.

I have a biopsy coming up soon. Can I donate now?

We are working on an interim solution for specimen donation while we finish defining the project.

I need more info or I want to participate. Whom should I contact?

Please feel get in touch with us at info@go2.org or (650) 598-2857 for more details, and/or specific questions.

Image Credits:

Figure 1: Sara M. Nolte (used with permission of Signals)

Figure 2: Jackson Laboratories (used with their permission)